What Mozambique’s ancient organic-walled microfossils reveal about the Permo-Triassic extinction

In northern Mozambique, the Maniamba Basin’s K5 Formation offers a window into Earth’s ancient past. Composed of sandstones, siltstones, claystones and coal, it preserves the dramatic Permian–Triassic transition 250 million years ago – a time of planetary transformation and Earth’s greatest mass extinction. Recent research in Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology uncovers fossilized pollen and spores from these strata, revealing how life rebounded after this cataclysm.

Through this new study, Nelson Nhamutole and Prof Marion Bamford of Wits University and their international team identified, for the first time, evidence of the Permo-Triassic transition in the Maniamba Basin based on organic-walled microfossils. Nelson explains the significance: “The Permo-Triassic event is a critical moment in Earth’s history, where 95% of ecosystems are believed to have gone extinct. Understanding these past changes in ecosystems could help us predict future changes in the world we live in today.”

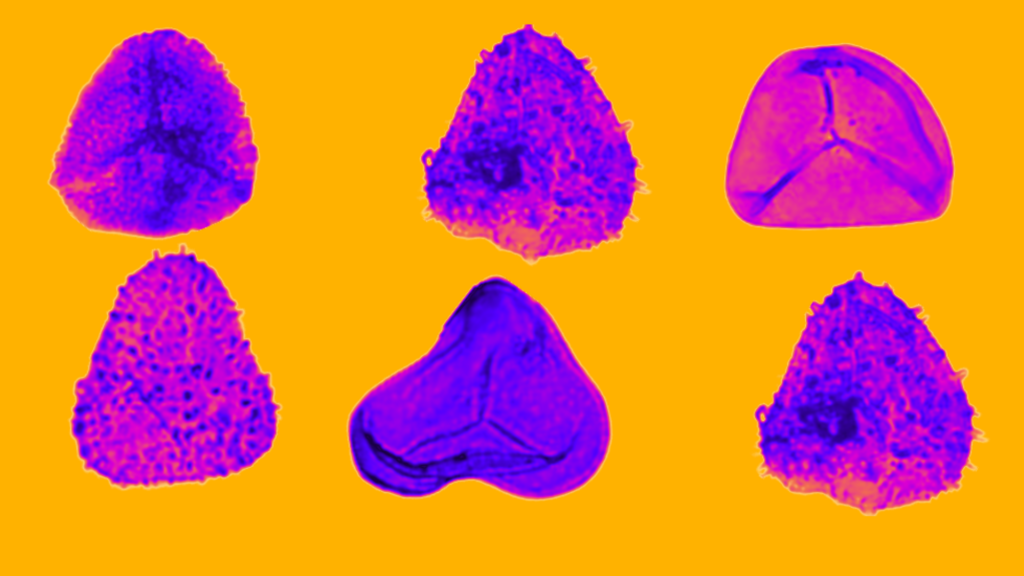

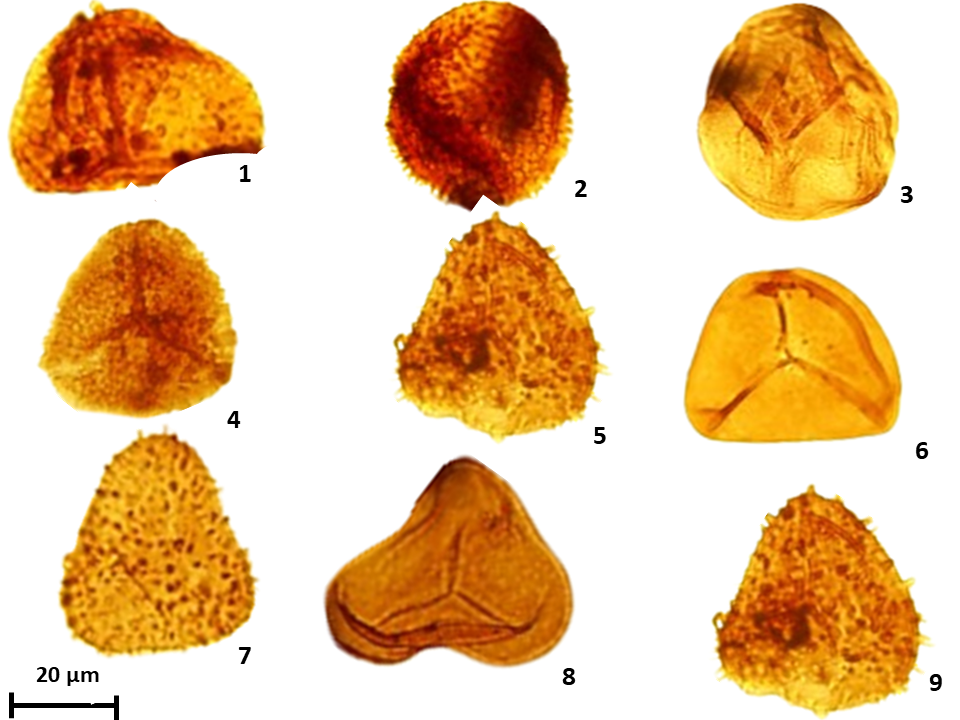

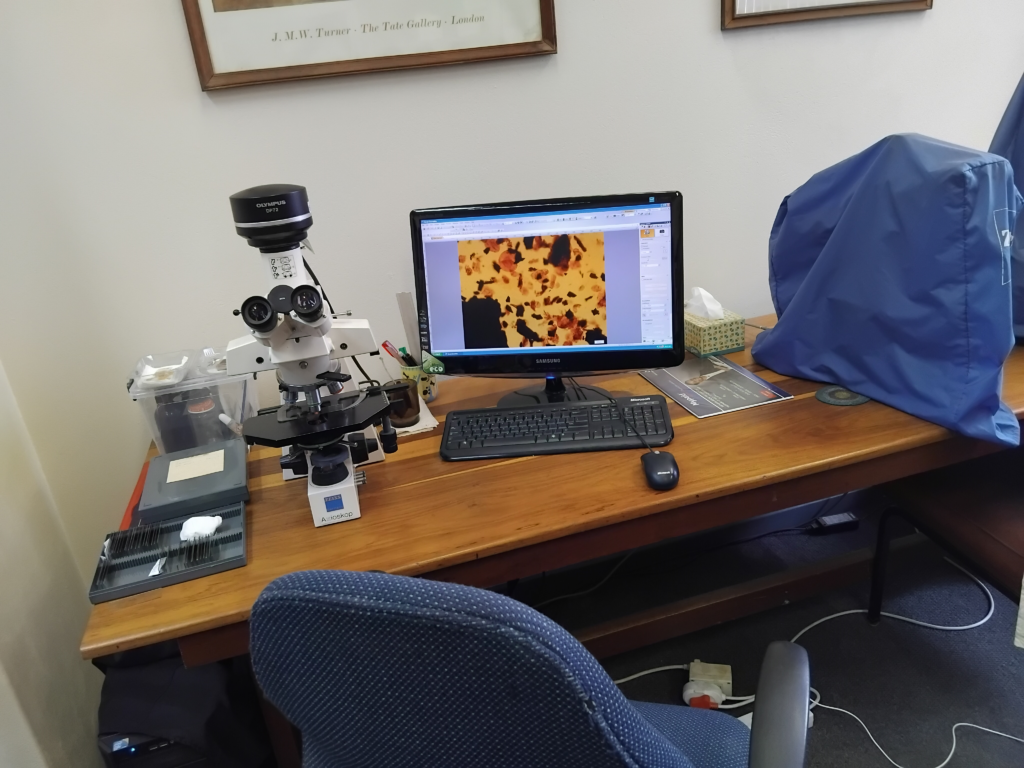

The study meticulously analysed two borehole cores to uncover fossilised pollen, spores, and other plant microfossils (other organic matter) preserved in sedimentary deposits. The change in abundance and appearance or disappearance of these microfossils along the studied borehole cores has revealed a dramatic environmental shift. Four distinct assemblages were identified, revealing a transition from lush, humid Late Permian vegetation (approximately 259–252 million years ago) to sparser, drought-adapted ecosystems in the Early Triassic (about 252–247 million years ago). By comparing these findings with other Gondwana basins, the researchers pieced together a broader picture of climate shifts and plant recovery during one of Earth’s most turbulent eras.

Nelson finds it exciting that the research offers new insights into the Maniamba Basin’s geological timeline: “This research shows that the rocks from the K5 Formation were likely deposited during the latest Permian (around 259 million years ago), which challenges earlier assumptions.” The researchers also found that regions like South Africa’s Balfour Formation, Madagascar’s Sakamena Group, and India’s Raniganj Formation were covered by the same vegetation about 254 million years ago. “It’s also worth noting that the thick coal seams in the basin could spark interest in coal bed methane exploration as the world moves towards cleaner energy sources,” he says.

The Permian–Triassic extinction, also known as the Great Dying, was Earth’s most devastating extinction event, wiping out 90% of marine species and 70% of land species. This catastrophe, likely triggered by massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia, unleashed climate chaos, acid rain, and ocean oxygen loss (anoxia), leading to widespread ecological collapse.

Amid this global turmoil, Mozambique’s Maniamba Basin preserves a remarkable record of life. The lower layers of the K5 Formation reveal tiny pollen grains from ancient conifers and other seed plants, suggesting the area was once covered by vegetation that thrived under warm and humid conditions. However, the upper sequence of rocks tells a different story. Fossil pollen from the Early Triassic reflects a shift to drier, more arid conditions, with drought-tolerant plants becoming dominant. This change mirrors similar pattern across much of Central Gondwana, highlighting a continent-wide response to the upheaval.

The microfossils from the Maniamba Basin also offer unique insights. Even more intriguing is the occurrence of unidentified pollens species, which may possibly represent signals of ecosystem recovery. These findings have the potential to reshape our understanding of how life rebounded after the Permian extinction.

One of the most exciting discoveries was pinpointing the Permian–Triassic boundary within the Maniamba Basin. Although barren zones in the fossil record made precise identification challenging, the researchers found specific depths where plant abundance declined sharply, coinciding with the first appearance of stratigraphically important Early Triassic pollen. Nelson describes the challenge: “Some samples during lab procedures were barren of microfossils due to poor preservation, which complicated tracking vegetation changes. However, through experience and meticulous observation, we successfully reconstructed the vegetation history and dated the rocks intercepted by the boreholes.”

The research team sees this as just the beginning. Nelson shares his vision for the future: “It would be fascinating to complement this biostratigraphic information with additional data, like carbon isotopes, molecular fossils (biomarkers), and radiometric dating. This could help build a highly refined chronostratigraphic framework to deepen our understanding of Gondwana correlations.”