Tiny Titans of the Permian: New anatomical description of the ‘dwarf’ pareiasaur Nanoparia luckhoffi from the Karoo Basin

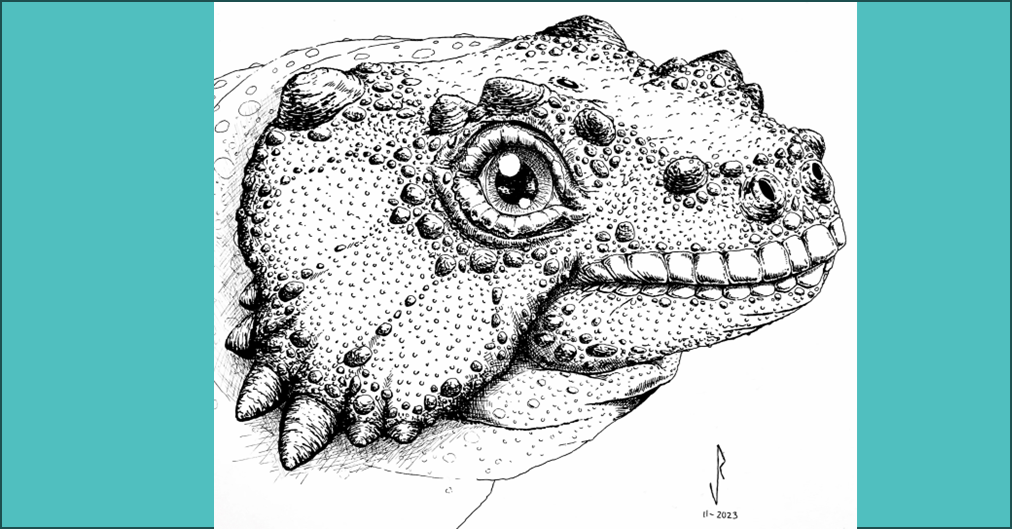

Artistic reconstruction of Nanoparia luckhoffi (RC 109) by Viktor Radermacher. Image credit: Published in Van den Brandt et al. 2024. https://doi.org/10.4072/rbp.2023.4.04

From the depths of South Africa’s Karoo Basin, a remarkable discovery has emerged from the Permian period’s dusty archives, presenting a tale of miniature giants in a world long gone. The late Permian ‘dwarf’ pareiasaur (meaning ‘cheek lizards’), Nanoparia luckhoffi, has been given new life through the meticulous efforts of palaeontologists Dr Marc Van den Brandt and his team. Until now, this species, which lived around 255 million years ago in what is now South Africa, had eluded a full anatomical description since its initial erection by Robert Broom in 1936. Van den Brandt and his team have changed that by providing a comprehensive cranial description and unveiling new diagnostic characteristics in their latest publication in Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. These insights enable palaeontologists to accurately identify and appreciate the nuances of thisdwarf pareiasaur like never before, and how it relates to its closest cousins.

Pareiasaurs, the family to which N. luckhoffi belongs, were unique parareptilian (or ‘near-reptiles’) herbivores that lived just before the Permian period ended. Despite their wide range and variety, much about dwarf pareiasaurs remained a mystery, overshadowed by their better-understood and larger relatives. However, this recent study puts Nanoparia in the spotlight by offering the first detailed description of its skull and a new diagnosis, helping us better understand its role within the pareiasaur family tree. The importance of this research goes beyond just one species. Nanoparia luckhoffi is identified as a ‘dwarf’ pareiasaur, a part of the Pumiliopareiasauria group of pareiasaurs that includes three species from South Africa and one from Brazil, which was connected to Africa at the time as the single southern land mass Gondwana. This indicates that the ‘dwarf’ pareiasaurs were spread across the southern supercontinent Gondwana, enhancing our knowledge of their global distribution. This work fills in gaps about N. luckhoffi, also contributing to our broader understanding of pareiasaur evolution worldwide.

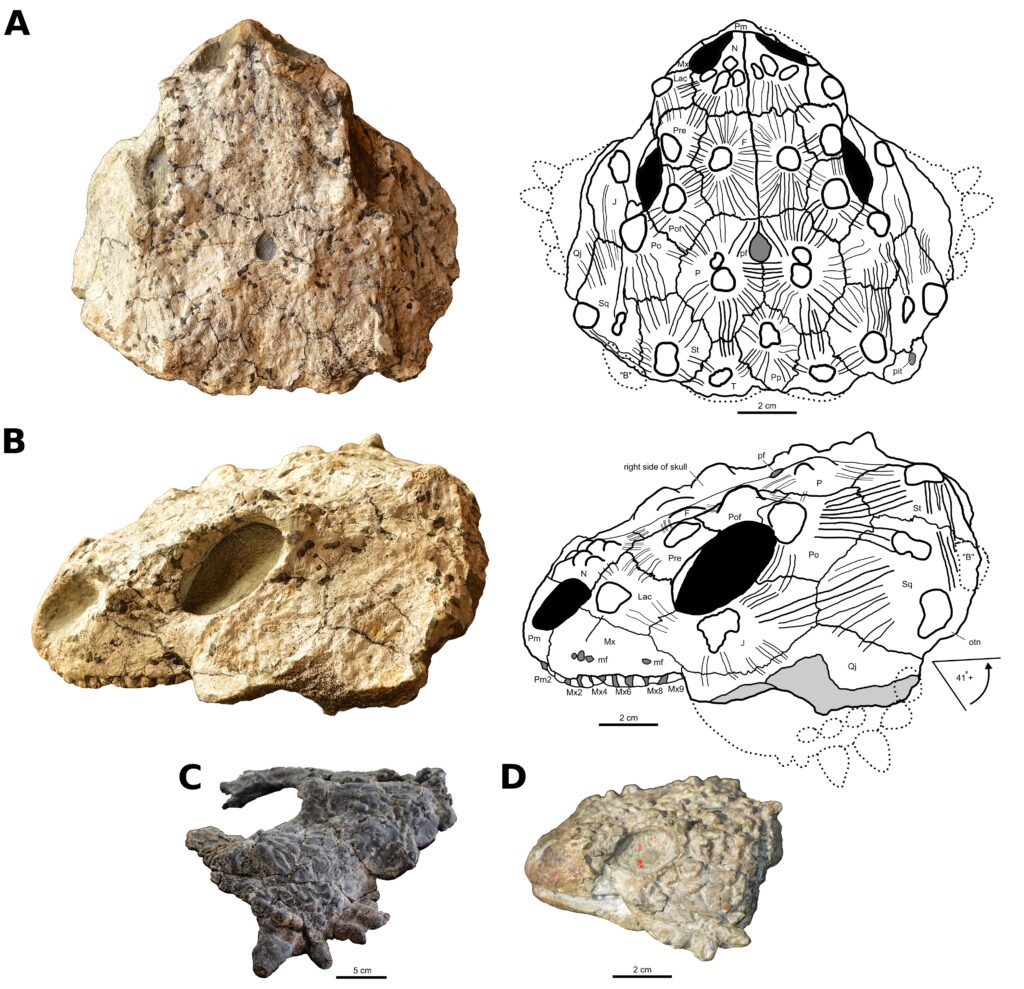

Van den Brandt and his team describe seven unique features (autapomorphies) of the dwarf pareiasaur, including a distinctive additional bone on the cheek, a unique notch on the palate, and an unexpected pronounced internal flange on the tabular bones, among others, after months of hard work. “Our technician, Justin Arnols, spent nearly 3 months preparing the fossil, cleaning off most of the remaining rock from the skull, which revealed seven new unique anatomical features that can now be used to positively identify specimens of this species for the first time,” says Van den Brandt. These characteristics distinguish this species from its contemporaries and suggest that the holotype specimen (the primary reference point for the whole species’ identity) is a juvenile. This discovery challenges previous assumptions and opens new avenues for understanding pareiasaurian diversity and evolution. “Justin’s meticulous preparation of the skull allowed us to discover the unique palatal notches and pronounced flange on the internal tabulars, features I have never seen before, even after studying hundreds of pareiasaur skulls and describing four species in detail, a eureka moment, and the reason we do science” says Van den Brandt.

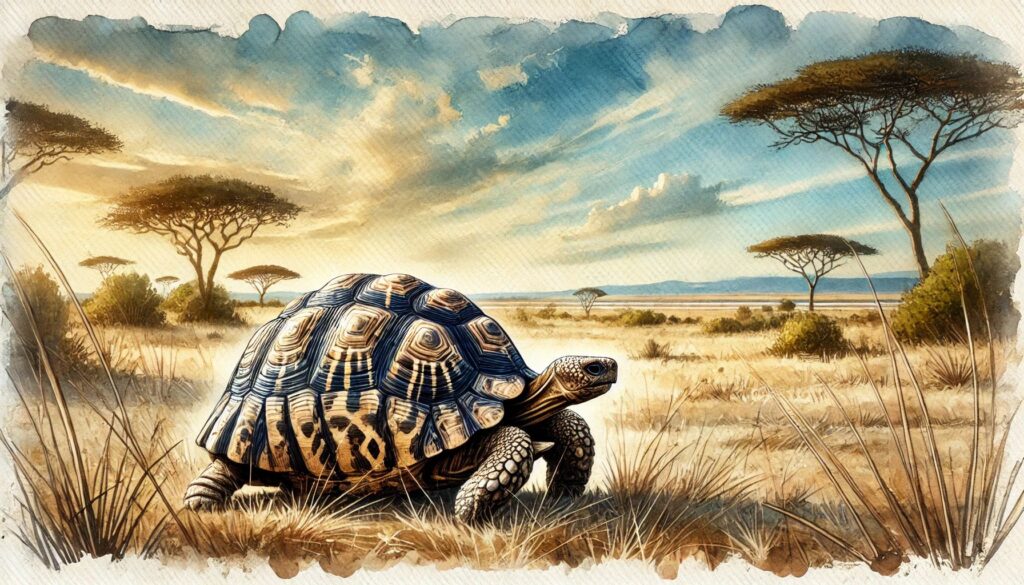

Although the cheek flanges of this dwarf pareiasaur specimen are largely missing, the research team ingeniously reconstructed its facial features by comparing it with closely related species. This comparative analysis enabled them to reimagine the dwarf pareiasaurwith pronounced cheeks adorned with bony protrusions along the back and bottom edges. To bring this vision to life, PhD candidate (in Palaeontology) and palaeoartist and Viktor Radermacher skilfully illustrated what the animal may have looked like in life, including these reconstructed cheeks, offering a fascinating glimpse into the appearance of this ancient creature.

By combining different sets of data, Van den Brandt and his team have now provided a clear roadmap for studying how pareiasaurs are related, especially highlighting the strong link between the South African and Brazilian species. This unified approach makes future research easier and helps palaeontologists around the world get a better picture of how these ancient reptiles lived and changed over time.

The journey to uncover the secrets of the dwarf pareiasaur and its relatives illustrates the dynamic nature of palaeontology, where each discovery builds on the last to deepen our understanding of Earth’s history. As research continues, especially into the skulls and body armour of other pareiasaurs, our grasp of this ancient world and its inhabitants will only grow more detailed and fascinating.

“This new research has significantly contributed to expanding our knowledge of the four ‘dwarf’ pareiasaurs,” says Van den Brandt. He is excited about future research and states, “Prof Cisneros has notably enhanced our grasp of the South American ‘dwarf’ pareiasaur species, and we’ve now made substantial progress with N. luckhoffi. The team of researchers are already delving into the anatomy of another South African ‘dwarf’ pareiasaur, Pumiliopareia pricei, focusing on its skull, teeth, and armour plates.”