Meet Dr Lynne Quick, a Senior Research Fellow from Nelson Mandela University’s African Centre for Coastal Palaeosciences

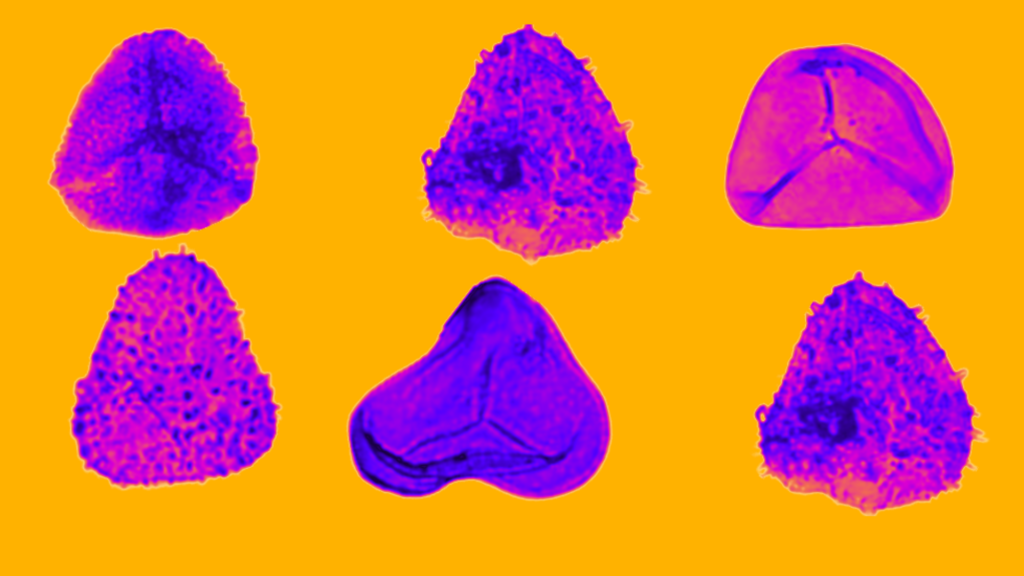

How pollen tells the story of evolving plant life and a changing climate.

Lynne Quick is not allergic to pollen, but even if she were, she would probably still be obsessed with these microscopic particles that can tell us so much about the past.

While hiking with friends in the wilderness areas of the Western Cape and Eastern Cape, Quick will often disappear to investigate a rock face in the distance, returning hours later, bloodstained, sweaty and – with luck – triumphant.

Triumph, on these occasions, means she has discovered another dassie midden: a mound of rock hyrax faeces and urine dating back up to 50,000 years and laden with pollen that helps to tell the story of evolving plant life and a changing climate.

Quick’s expertise in palynology, or the study of pollen grains, is rare in the world of palaeoscience, which in itself encompasses a relatively small group of academics in South Africa.

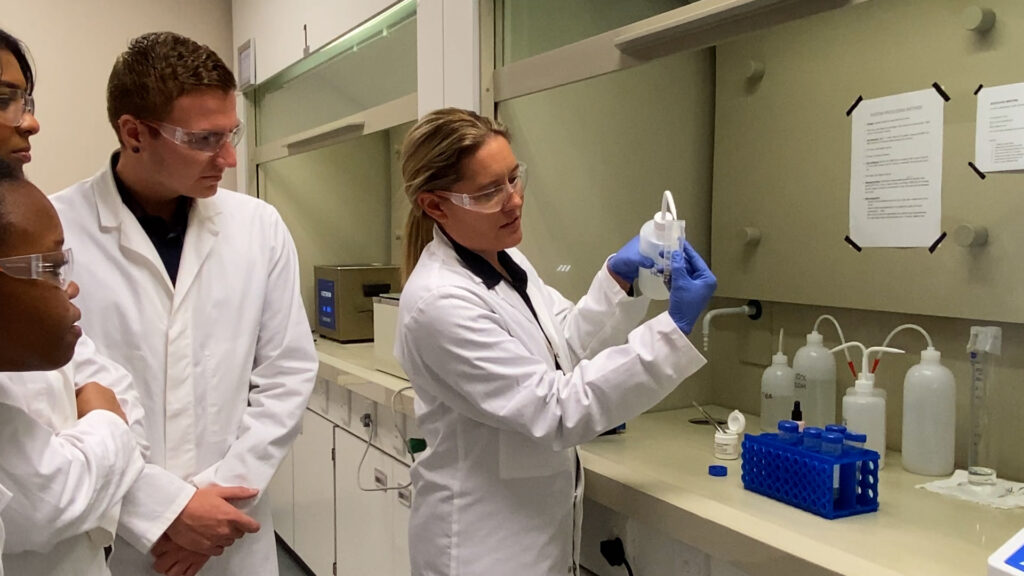

But judging by the list of students the senior research fellow supervises at Nelson Mandela University’s African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, she achieved one of her primary objectives when she arrived in Gqeberha in 2018: to attract talent, build expertise and create a centre of excellence.

Key to that process, says Quick, is a growing realisation in an era of alarming climate change that the past can teach us vital lessons about the present and the future.

“I think we were a bit guilty a couple of years ago of looking at the science in a very academic sense, and we’ve grown a lot in terms of application of the data,” she says.

“Now we’re engaging with conservation experts and climate modellers and realising that we can apply our data to how we’re managing the landscape now by bringing palaeoecology and ecology together.”

That was what was happening in 2022 when Quick took an odd picture which won 15 minutes of worldwide fame by being chosen as a runner-up in Nature’s annual #ScientistAtWork photographic competition.

The photograph showed Sparkles, an inflatable unicorn, being used by a doctoral student as a floating platform for a freeze-corer at Verlorenvlei on the west coast.

The unicorn was a spur-of-the-moment purchase when Quick thought she might need a flotation device during an earlier expedition in Pearly Beach. The objective was to extract a sediment core from a wetland, hoping that the pollen, fungal spores and charcoal it contained could help reconstruct the area’s ecological history.

Just as importantly, though, Sparkles and an American colleague’s inflatable Tyrannosaurus rex, Sprinkles, inject fun into what can be gruelling work in harsh and remote environments.

“I’m really trying to only work with people that are fantastic human beings, and I get on with,” says Quick.

This need to be outdoors saw Quick pivot into palaeoscience at the start of her honours course in environmental and geographical science at the University of Cape Town.

Keen to ensure her studies would lead to a job, she won one of a handful of coveted places on an environmental management course … and it lasted a day. “I listened to what we were going to be doing for the year, which was sitting behind a computer and writing reports, and I signed straight off,” she says.

“The head of the department, Prof Mike Meadows, said, ‘let’s go to the pub and talk about this’, then he said, ‘we’re doing these really interesting things in palaeoscience’.”

“It’s critical to have a sense of humour because out there in the field, nothing ever goes right. You have to overcome these challenges physically and mentally, and if you’re not having fun and you’re not within a good team, it’s really not worth it”

Dr Lynne Quick

The Quaternary palaeoecology course she ended up taking led to a Master’s, which had her crawling across dassie middens in the Cederberg, and a PhD in which she examined pollen from three wetlands on the southern Cape coast.

Meadows and UCT palaeoclimatologist Brian Chase, who co-supervised her doctoral studies, continue to be close and regular collaborators. Still, Quick says it’s another indicator of the limited size of the palaeo community in South Africa that she works more with foreigners than she does with locals.

By building a new, state-of-the-art palaeoecological lab at NMU and developing a research agenda with the help of grants from the likes of Genus, the National Research Fund African Origins Platform and the Australian Research Council Discovery Project, she hopes to change that picture.

“It’s just been great to build traction here at Mandela Uni, and I would like to keep going with that and show that while palaeoscience was very low on the radar a few years ago, we’re now becoming a contender,” she says.

Students who team up with her will be exposed to sites such as the Boomplaas Cave in the foothills of the Swartberg, the Succulent Karoo in Namaqualand. They’ll undoubtedly find themselves crawling over rock-hard dassie middens, helping to chainsaw off slices, then wrangling them down mountains and back to the ordered world of Quick’s microscope-lined lab.

After pandemic disruptions, says Quick, “things are cooking for us here”, and she has high hopes that a science faculty symposium she’s planning for later this year will tempt more students into the world of palaeo.

If students are really lucky, they might be able to take Sparkles for an outing. “It’s been quite a journey with her,” says Quick.