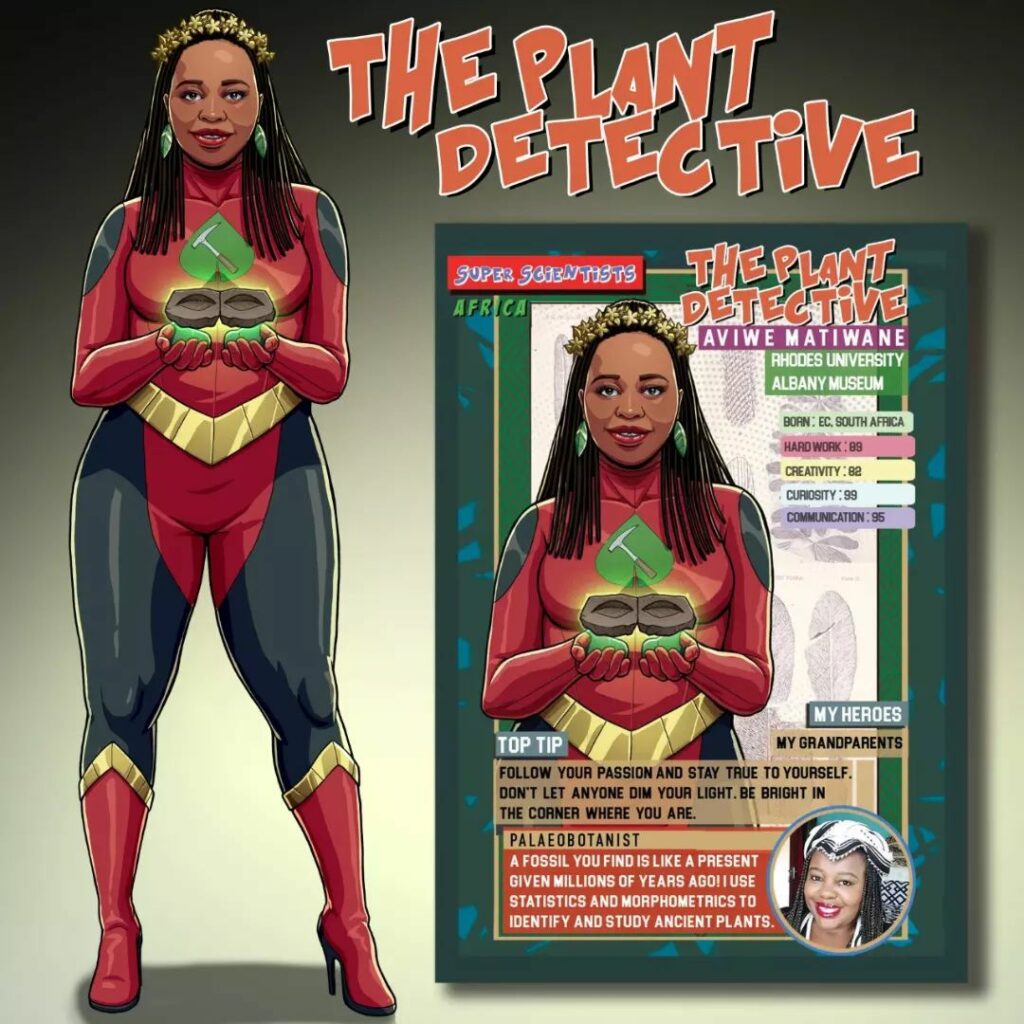

The Journey of ‘The Plant Detective’, Aviwe Matiwane

The plant detective SuperScientist Aviwe Matiwane explains her journey on her way to becoming one of three female Palaeobotanist in South Africa, as she inspires others to follow their passion even when it gets difficult.

Small bites

- Aviwe is one of only three female Palaeobotanists in South Africa.

- She was nominated as one of The Mail & Guardian’s 200 Young South Africans and became an InspiringFifty South Africa winner.

- Her career was family-inspired, and also by accompanying one of the female palaeobotanists, Dr Rose Prevec, into the field.

For the love of flora

Aviwe Matiwane is known as ‘The Plant Detective’ in the SuperScientists playing cards series and on social media, and as ‘mom’ to 14 four-footed children, she calls her ‘science pups’.

Aviwe Matiwane, Rhodes University and Albany Museum PhD Palaeobotany candidate and lecturer, has an ardent love of the natural world, whether living or fossilised – and has since she was a little girl. “As a child, my grandfather, a self-taught botanist interested in medicinal plants, would take me along on his walks in the forest near our farm in Lower Ngqwara, a rural Eastern Cape town. His love of flora and my aunt’s knowledge of the natural world as a sangoma planted the seeds for my future career.”

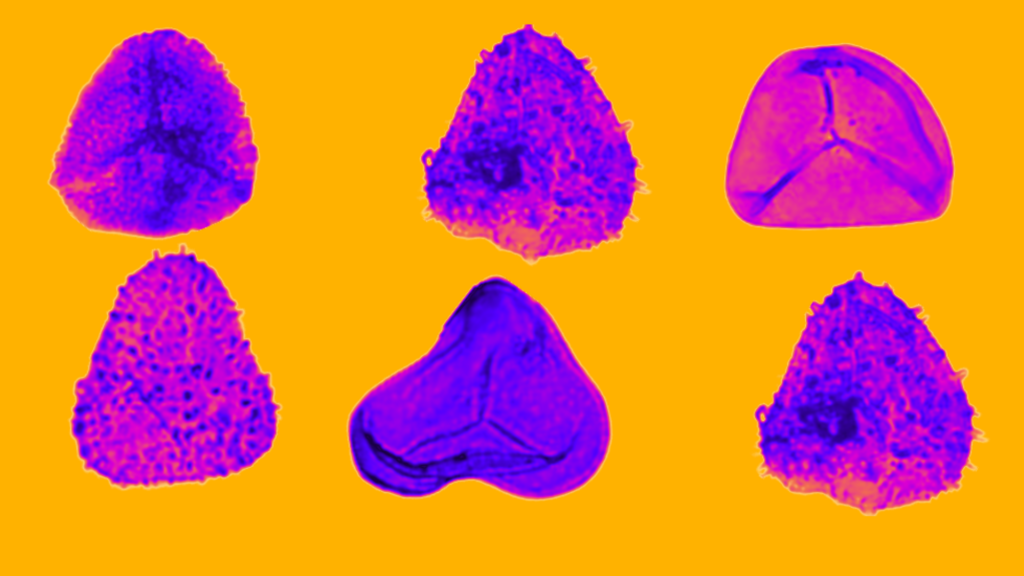

But it would take her some time to find this life path. “I first enrolled to study archaeology because I didn’t even know you could study plants at that point,” she laughs, shaking her head. She soon switched to studying biological sciences (botany and zoology), followed by honours and a master’s degree in botany. “During my final year, I encountered plant fossils for the first time during a meeting with one of my facilitators. I was so fascinated by them that he introduced me to Dr Rose Prevec, a Palaeobotanist and curator in the Department of Earth Sciences at the Albany Museum.”

Aviwe would accompany Dr Prevec on field trips and decided this would be her future, too. Soon after she completes her PhD, for which she received a bursary from GENUS (DSI-NRF Center of Excellence in Palaeosciences), she is one of only three female palaeobotanists in the country.

That is why she is so passionate about science communication. “I never thought I would be in this position, championing science communication, because I am petrified of speaking in front of people,” she laughs. But after reaching the top 10 in the FameLab science communication competition in 2017, she realised she has an aptitude for it. She has since become a well-known science communicator on social media channels, was nominated as one of The Mail & Guardian’s 200 Young South Africans in 2018, and became an InspiringFifty South Africa winner in 2020.

She also uses this platform to speak out about discrimination – something at the front of her mind not only as a woman and a minority in a white-dominated field but also as a scientist from a developing nation. Her recent paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, “Colonial history and global economics distort our understanding of deep-time biodiversity”, explores this problem. According to the authors’ findings, researchers based in countries in Northern America and Western Europe – despite developing nations’ rich fossil heritage, generate 97% of palaeontological data. “Researchers from wealthy countries often come to these areas, work on the fossils, and then retain the information as theirs without acknowledging that the work was done in a developing country. It shows how money can open doors for research and how those people can then become gatekeepers of the knowledge.”

She says that one of the many keys to changing this narrative is to make local scientists and their work more visible. “Role models are crucial to growing the field, and that visibility can generate more interest, get more people in the field, and increase funding and study in developing countries like ours.”