Tall Grass, Long Legs – A New Lovebird Species From the Cradle of Humankind

Life reconstruction of Agapornis longipes feeding on the ground in the Early Pleistocene of the Cradle of Humankind (Gauteng, South Africa) during the dry season (Artwork by Martina Cadin).

In the lush, ancient grasslands of what is now South Africa, a small, colourful parrot once moved quietly through patches of tall grass, sharing its world with early hominins and giant mammals. This newly discovered extinct lovebird, Agapornis longipes, has been brought to light thanks to an exciting fossil find in the Cradle of Humankind by an international team with researchers from South Africa, Italy, Germany, and France, led by the University of Torino, Italy. Their findings, published in Geobios, reveal a glimpse of this lovebird’s past and the ecological changes of the Plio-Pleistocene, a period stretching from 5.3 million to 11,700 years ago.

The fossil remains were uncovered at three major South African fossil sites: Kromdraai, Cooper’s Cave, and Swartkrans, all within the Cradle of Humankind. These sites are famous for hominin fossils, but birds like A. longipes also played a crucial role in the ancient ecosystem. Dr Bernard Zipfel from the Evolutionary Studies Institute at Wits expressed his excitement about the discovery: “As a co-permit holder of Kromdraai, I was thrilled to learn that the primary specimen and additional examples of A. longipes were found at this site.” He added, “This discovery has made me more aware of the importance of birds in the fossil record. In recent field seasons, alongside Jose Braga, we uncovered several bird remains, and I look forward to Dr Pavia studying them to further our understanding of fossil birds.”

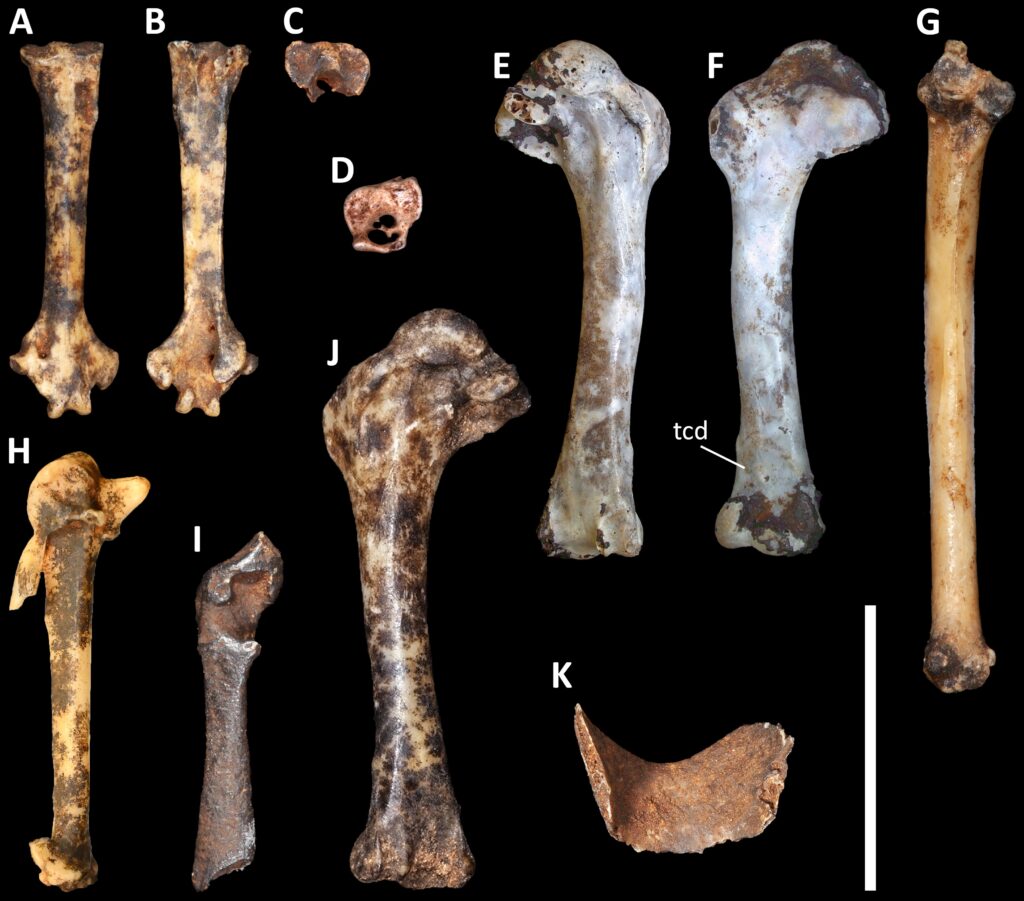

What sets Agapornis longipes apart is its unique leg structure, with a much longer tarsometatarsus (leg bone) compared to modern lovebirds, suggesting it was well adapted for life on the ground. While today’s lovebirds flit between trees and short grass collecting seeds and fruit, A. longipes likely foraged on the ground, navigating the tall, dense grasslands that characterised its environment. “The newly discovered lovebird species was native to wooded savannas, but its longer legs suggest an adaptation to the increasingly open environments that emerged during the Early Pleistocene,” explains lead author Dr Marco Pavia. Fossil remains, including wing and leg bones, a fragmentary mandible, and part of a coracoid (a shoulder bone), were key to identifying the bird and shedding light on its lifestyle. These fossils suggest A. longipes was slightly smaller than modern lovebirds, with proportionally shorter wings to match its elongated legs. “Lovebirds feed mainly on grass seeds and fruit from the ground, so we see the longer legs as an adaptation to navigating taller grasses,” adds Dr Pavia.

Identifying the exact species was another hurdle. “Identifying the remains as a lovebird was straightforward, but determining the exact species was more challenging,” Dr Pavia adds. Access to well-preserved bones, previously studied by Pocock at Wits University’s Evolutionary Studies Institute, was critical. “Comparing the fossil bones to modern lovebird species was tricky, but thanks to colleagues at institutions like the Ditsong Museum in Pretoria, we were able to make the necessary comparisons.”

Interestingly, A. longipes inhabited a landscape not too different from today’s South African grasslands, though the species that roamed alongside it were very different. Over time, as the climate and ecosystems shifted, the lovebirds—along with many other species—disappeared, likely due to changes in food availability or competition.

This discovery offers critical insights into the biodiversity and ecology of ancient southern Africa. Each fossil adds a piece to the puzzle of how ecosystems evolved over millions of years. By studying extinct species like A. longipes, scientists can track environmental changes and how ancient creatures, including humans, adapted.

Scientists have long believed that ancient lovebirds existed in Africa, as parrots colonised the continent over 24 million years ago. However, fossil evidence of African parrots, especially lovebirds, is rare. A. longipes joins a small group of ancient lovebirds known from fossils, including Agapornis attenboroughi, another extinct species from South Africa named after Sir David Attenborough.

Dr Bernard Zipfel expressed his anticipation for future discoveries: “I look forward to the bird remains from the last few field seasons being formally studied and to the exciting finds we will make in the future.”

“The study of these lovebirds is complete, but the data will be valuable for future research on other fossil parrots from Africa,” says Dr Pavia. “It will also aid in comparisons with any new fossil remains discovered at various sites in the Cradle.”