Palaeoanthropology Makes South Africa Proud: Local Fossil Record Sheds New Light on Human Evolution

New research from South Africa’s Sterkfontein Caves reshapes our understanding of early human diets.

South Africa’s world-famous fossil record has again placed the country at the centre of a major scientific discovery. New research, published in Science, reveals that Australopithecus, one of our earliest human ancestors, consumed little to no meat, challenging long-held assumptions about the role of animal protein in human evolution.

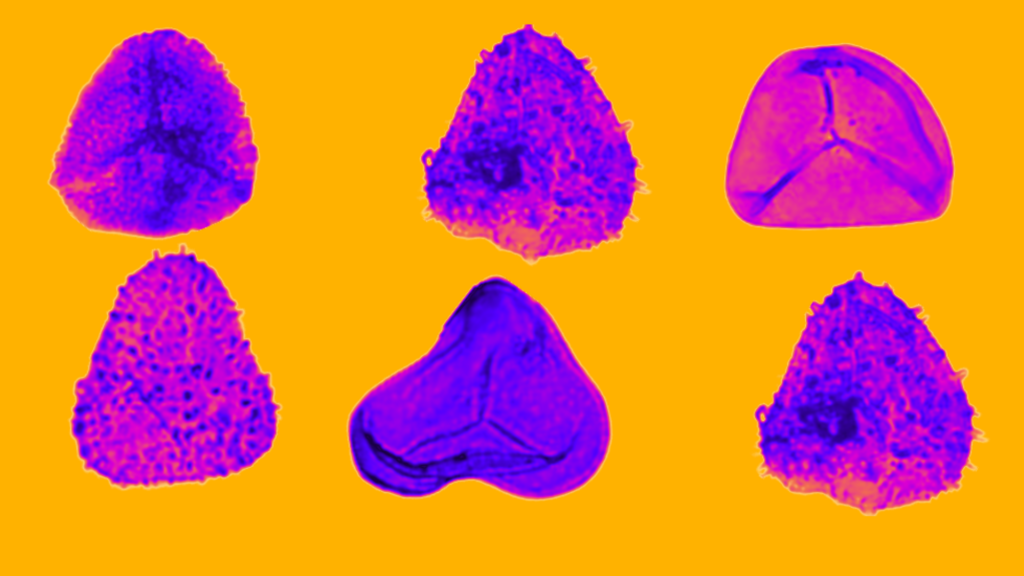

This discovery was made possible through cutting-edge nitrogen isotope analysis of fossilized tooth enamel, a technique that allows researchers to unlock dietary secrets from millions of years ago. Crucially, the study relied on fossils from Sterkfontein Caves, part of South Africa’s renowned Cradle of Humankind, reinforcing the country’s global leadership in palaeoanthropology.

“South Africa holds the largest collection of fossil hominins, but we lack the technology for advanced analysis. That’s why collaboration with international teams is key,” says Professor Marion Bamford, a leading South African palaeobotanist and co-author of the study.

The Sterkfontein Caves have yielded some of the most important hominin fossils ever discovered, including Mrs. Ples and Little Foot. Thanks to advanced geochemical techniques, these fossils continue to reshape the story of human evolution.

“Unlike East African sites where fossils are scattered, ours are preserved in karstic caves. Sterkfontein has the richest and oldest deposits, making it a crucial site for understanding our past,” explains Bamford.

The research team, led by Dr Tina Lüdecke of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and the University of the Witwatersrand, analysed nitrogen isotopes in the tooth enamel of seven Australopithecus individuals. Their results suggest that these early hominins primarily consumed plants, with little to no evidence of regular meat consumption.

This challenges the idea that primarily meat consumption drove early human evolution. Instead, Australopithecus appears to have been an opportunistic forager, relying on plant-based foods rather than hunting large mammals. “This gives us a clearer picture of Australopithecus’ diet. Meat-eating existed in later species, but when did it start? Likely not with them,” says Bamford. Although mostly plant-based, their diet may have included insects or eggs.

This research highlights South Africa’s key role in palaeoanthropology. The Cradle of Humankind remains a treasure trove of discovery, attracting international collaboration and investment, “Most South Africans know little about our fossil heritage. We need to promote it through schools, media, and museums while securing funding for research and conservation,” says Bamford.

One challenge is ensuring local scientists remain at the forefront, “International teams have more funding, so critical research often happens overseas. We need to train and support our own students to lead future discoveries,” she stresses.

The researchers plan to expand their work, analysing fossils from other sites in Africa and beyond to determine when regular meat consumption became a staple in human evolution, “Excavations at Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, and other sites continue to reveal new fossils. With advancing techniques, we expect even more exciting discoveries,” says Bamford.

She is particularly interested in how ancient environments shaped human evolution. “I find it fascinating. We’re slowly piecing together the environmental context that shaped our ancestors,” she concludes. As palaeoanthropology continues to evolve, one thing remains certain: South Africa is at the epicentre of one of science’s most important stories—the story of us.