Moschorhinus kitchingi: The Ancient Stocky Survivor of the Karoo

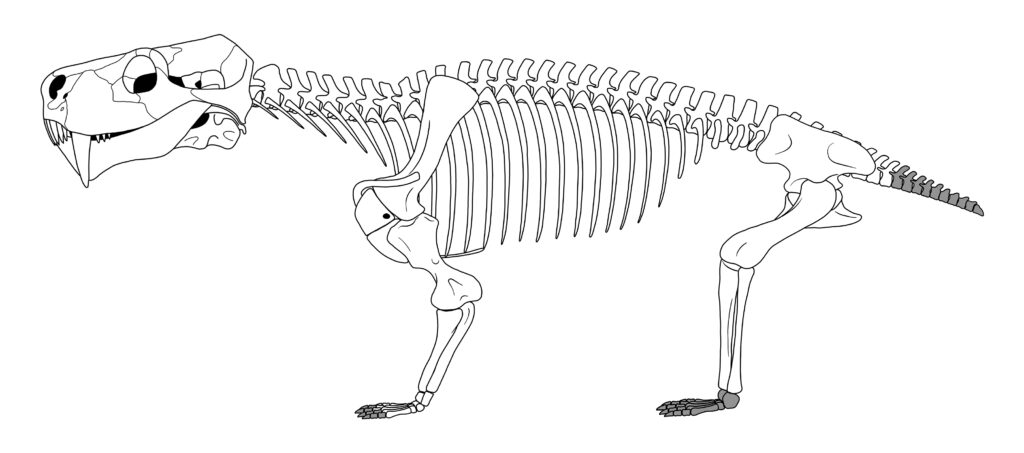

The skeleton of Moschorhinus kitchingi, a prehistoric therapsid. Photos show NMQR 3351, the largest known specimen, from both the top (dorsal) and bottom (ventral) views. Photographs by Brandon P. Stuart.

Imagine a world on the brink of collapse: volcanic eruptions spewing toxic gases, oceans turning acidic, and up to 90% of Earth’s species vanishing in the blink of an eye. This was the reality at the end of the Permian Period, around 252 million years ago, during Earth’s most catastrophic mass extinction event. Yet, amid this global upheaval, a stocky predator (with a body length of just over a metre) known as Moschorhinus kitchingi managed to survive and thrive, staking its claim as one of the top predators in the aftermath. For the first time, scientists from the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Southern California have offered a detailed look at the skeleton of Moschorhinus kitchingi beyond just its skull, by studying multiple fossil specimens from collections in South Africa.

This research, led by Wits PhD student Brandon Stuart, with Adam Huttenlocker and Jennifer Botha, and published in PeerJ, reveals how Moschorhinus kitchingi evolved its body structure to withstand the extreme conditions that led to the extinction of many other species. Unlike the more charismatic group of prehistoric animals, the dinosaurs, which wouldn’t appear until millions of years later, Moschorhinus belonged to a group of prehistoric creatures known as therocephalians.

The Permo-Triassic extinction is often compared to modern-day climate change due to the rapid shifts in global temperature and atmosphere. By studying survivors like Moschorhinus, scientists can gain a better understanding of which traits and behaviours helped species endure during periods of mass extinction. This, in turn, could offer clues to how current species might adapt—or fail to adapt—to our rapidly changing world.

What’s particularly interesting about Moschorhinus is how it differed from other top predators of its time, such as the gorgonopsians, which were more slender and agile. While both groups likely shared similar ecological niches, the subtle differences in their postcranial anatomy suggest that Moschorhinus might have occupied a slightly different role in its ecosystem, perhaps focusing on different prey or hunting strategies. This concept, known as niche partitioning, might have been key to its survival when so many others perished.

“Therocephalians are a fascinating group of ancient creatures closely related to the early ancestors of mammals,” says PhD student Brandon Stuart. “ Previous studies mostly focused on their skulls, so much about their growth and way of life was still unknown. But now, we’re finally getting a clearer picture of what this remarkable survivor was like,” says co-author Professor Jennifer Botha from the University of the Witwatersrand.

The Moschorhinus fossils were found in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. The Karoo Basin is a significant geological formation known for its rich fossil deposits, particularly those from the late Permian to Early Triassic periods. The study reveals that Moschorhinus had a uniquely stocky build, characterised by a particularly strong and thick-set skeleton. Its robust scapula (shoulder blade), humerus (upper arm bone), and femur (thigh bone) suggest that it was well-equipped to grapple with and overpower its prey. “This physical strength likely gave it a significant advantage in the late Permian, where competition for survival was fierce,” says co-author Adam Huttenlocker. A short and powerful skull with enlarged canines further indicates that Moschorhinus was an adept hunter, capable of taking down sizable prey with its muscular build. However, it was not easy. “This research was challenging because so little work has been done on the bones beyond the skull for therocephalians,” explains Brandon Stuart. “It made it difficult to compare certain features of these bones to those of closely related species and other similar groups, so we are hoping that this work will set the foundation for future studies on the skeleton of mammalian ancestors.”

“By studying the bones beyond the skull, we can uncover the true size and appearance of these ancient creatures,” he elaborates. “This insight not only helps us build a more complete picture of these prehistoric animals but also allows us to understand the diversity within species that lived together. These differences can reveal fascinating details about their biology, behaviour, and how they thrived in their environments.”

The research also highlights the evolutionary resilience of therocephalians, a group that has been somewhat overshadowed by the more famous dinosaurs and early mammals. The study’s detailed analysis of Moschorhinus‘s skeleton not only fills a gap in the fossil record but also underscores the importance of these often-overlooked creatures in our understanding of prehistoric life. “We’re excited to dive deeper into the untold stories of non-mammalian therapsids by exploring more of their bones beyond the skull,” says Brandon Stuart. “By uncovering hidden details in their skeletons, we can gain new insights into their anatomy and learn how these variations reveal secrets about their ecology and biology.”